5 recent findings that may surprise you

Shawn Hempel/stock.adobe.com.

With science news laser-focused on the coronavirus pandemic, research on other topics has taken a back seat. Here are some recent study results that may come as a surprise.

1. You can be a “healthy” weight but metabolically unhealthy.

Think your risk of type 2 diabetes is near zero because your weight is in the normal range? Not quite.

“The most important thing you can do to lower your risk of type 2 diabetes is to avoid weight gain and lose excess weight,” says JoAnn Manson, chief of preventive medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

That’s because roughly nine out of ten people with diabetes are overweight or have obesity. But weight isn’t the whole ballgame.

Manson and her colleagues tracked roughly 17,000 postmenopausal women in the Women’s Health Initiative for 16 years.1 Along with weight, they looked at women who were “metabolically unhealthy”—that is, they had at least two of these four risk factors:

- Fasting blood sugar: at least 100 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL), or on drugs to lower blood sugar;

- Blood pressure: at least 130 systolic or 85 diastolic, or on drugs to lower blood pressure;

- Triglycerides: at least 150 mg/dL; and

- HDL (“good”) cholesterol: below 50 mg/dL.

“By far, the lowest-risk group had both a normal weight and were metabolically healthy,” says Manson, who is also a professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Only 162 of the roughly 3,200 women in that group were diagnosed with diabetes during the study.

However, the risk roughly doubled for women with a healthy weight who were metabolically unhealthy. Ditto for metabolically healthy women who had excess weight.

Not surprisingly, “metabolically unhealthy women with excess weight had more than four times the risk of type 2 diabetes,” notes Manson.

What do risk factors like blood pressure or triglycerides have to do with diabetes?

“If you have a cluster of cardiometabolic abnormalities like high triglycerides, a low HDL, and high blood pressure, it’s almost always a marker of insulin resistance,” explains Manson.

That is, it’s a sign that your insulin is no longer efficiently lowering blood sugar by admitting it into cells.

Researchers have some clues about what causes insulin resistance—often associated with the metabolic syndrome—but questions remain.

“The inflammation associated with abdominal fat appears to play a role,” says Manson. And women tend to gain more of that deep belly (visceral) fat after menopause.

“It makes a strong case for measuring waist circumference in clinic visits,” says Manson.

“If people have an expanding waist or elevated triglycerides or their blood pressure is creeping up,” she adds, “they may have added incentive to be more active, to eat a healthier diet, and to lose weight. That would also help reduce their risk of heart disease and stroke.”

The good news: “About 90 percent of type 2 diabetes cases could be prevented if people could maintain a healthy weight, stay physically active, not smoke, eat a diet that’s high in fruits and vegetables, and consume good fats rather than bad fats, whole as opposed to refined grains, and fewer sugar-sweetened beverages and refined sugars,” says Manson.2

2. Muscle strength drops rapidly in your 80s.

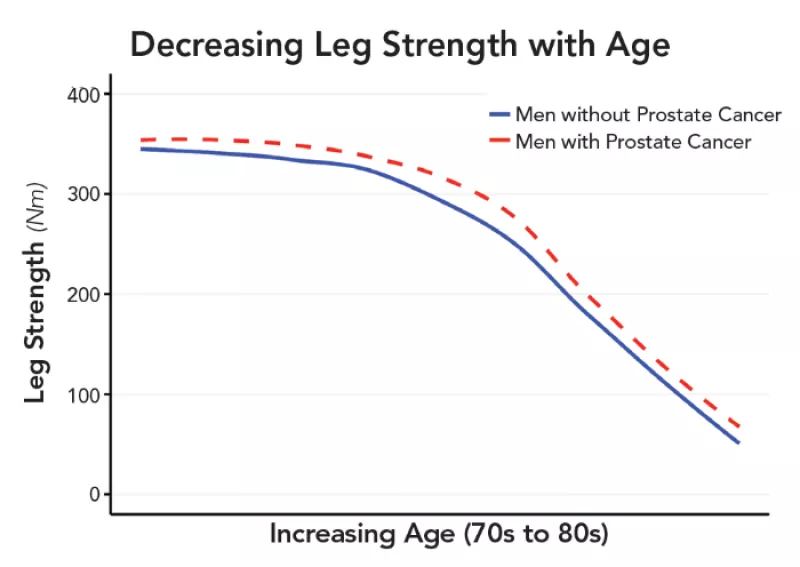

It’s no surprise that most people lose muscle strength as they get older. But when researchers tracked 585 80-year old men, they saw a whopping 70 percent loss of quadriceps (thigh muscle) strength over a seven-year period once men reached their 80s.3

“The fact that normal aging men experience such a significant decline in strength over time is quite important,” says Alexander Lucas of Virginia Commonwealth University, who led the study. In contrast, the men had lost only 7 percent of their quad strength over the initial seven years when they were in their 70s.

The study looked at 117 men with prostate cancer and 468 similar men without. “We expected to see a greater decline in strength in the men with prostate cancer, because of a variety of treatments they receive,” says Lucas. But they saw the same decline, cancer or no cancer (see graph).

And these guys were in better shape than many older people.

“The men were enrolled in the Health, Aging and Body Composition study, which selected people who were free of disabilities at the start of the study, so we could see how things changed as they aged,” explains Lucas.

What could explain such a dramatic loss of strength?

“Older men may lead more sedentary lifestyles,” says Lucas. “So they may lose fitness, which exacerbates the loss of muscle mass.”

But muscle strength drops about three times more rapidly than muscle mass.4 It’s not clear why.

“With aging, people start to put on body fat and lose lean tissue, and some of that fat is deposited between the muscle fibers,” explains Lucas. “The fat affects how well the muscle is able to contract.”

The nerves that make muscles contract may also play a role.

“Each muscle group is innervated by motor neurons,” says Lucas. “If you’re not active, you may lose the ability to effectively activate motor neurons.”

Would strength training slow the loss of strength? “Absolutely,” says Lucas.

In a study of 42 men and women aged 70 to 89, those who were randomly assigned to a control group lost 20 percent of their muscle strength (for a given muscle mass) after a year, while those who were assigned to strength, aerobic, flexibility, and balance training lost no muscle strength.5 The control group also gained muscle fat.

“The more muscle you have by age 80,” says Lucas, “the better off you are, because if you already have deficits in your 70s, they can curb your independence and quality of life from that point on.”

Strength ought to be part of an annual checkup, he adds.

“If you’re told, ‘Since the last time we saw you, you’ve lost 20 percent of your strength, so you need to do something about it,’ that could make a difference.”

3. Beef doesn’t beef up your muscles.

“Get your strength from beef,” says beefitswhatsfordinner.com, a website run by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association.

Does beef—or extra protein from any food—boost your strength?

In May, researchers reported the results of a study (funded by the Australian meat industry) that enrolled 145 older adults in a supervised strength-training program three days a week.6

After six months, those who were randomly assigned to eat two servings of lean red meat on each day they did strength training gained no more muscle or strength than those who ate two servings of rice, pasta, or potato instead.

“More and more evidence is showing that there isn’t a lot of benefit from extra protein, whether you’re engaged in resistance training or not,” says Bettina Mittendorfer, professor of medicine at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.7

A possible exception: young adults.

“The early studies were done in young, college-aged people,” notes Mittendorfer. “If you train as much as possible and get extra protein while you’re still in that growth phase, you can see a benefit. But in middle-aged or older people, it’s very hard to find studies that show a benefit.”

And if they do, it’s usually minor.8

For example, the same Australian researchers found a statistically significant effect on lean body mass in an earlier study.9 “But when you do the math, it comes out to about a 1 percent difference,” explains Mittendorfer. “That’s unlikely to have a clinically meaningful impact.”

And that’s the bottom line. “Even if studies find a small increase in muscle or lean body mass, most don’t find an increase in strength or physical function, which is the ultimate goal,” she says.

Why doesn’t more protein help?

“The majority of people, including healthy, free-living older adults, get enough protein,” says Mittendorfer.

On average, women get 35 percent more—and men about 65 percent more—than the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA), and both reach higher targets proposed by some experts.

Only 19 percent of women and 13 percent of men over age 70 get below the RDA—0.36 grams of protein for every pound you weigh.10 For someone who weighs about 150 pounds, that’s roughly 54 grams of protein a day, or 18 grams per meal.

“That comes down to a deck-of-cards-size piece of chicken breast at each meal,” says Mittendorfer. “It’s a small amount. We’ve become desensitized to what a normal amount of protein is.”

4. More vitamin D isn’t necessarily better.

“Bone health,” says CVS brand vitamin D, which comes in five doses—400 IU, 1,000 IU, 2,000 IU, 5,000 IU, and 10,000 IU.

Whoa. The Recommended Dietary Allowance is only 600 IU a day up to age 70 and 800 IU over 70.

Do your bones need doses in the thousands?

The VITAL trial randomly assigned 25,871 people to take 2,000 IU of vitamin D or a placebo every day for five years. Roughly 770 of the participants had their bone mineral density tested when they entered the study and again after two years.11

“Overall, taking vitamin D did not improve bone mineral density,” says Harvard’s JoAnn Manson, who led the main trial.

Vitamin D is essential for protecting bones, she adds. “It’s important not to be low, but more is not necessarily better.”

What’s the bottom line?

“We’re not recommending that everyone start taking high doses of vitamin D,” says Manson.

“If you start out at what’s already being recommended, you’re not likely to derive benefits for bone health by taking more.”

Megadoses may even weaken bones. In 2019, Canadian researchers reported that among 303 middle-aged and older adults (none were deficient in vitamin D), those who were randomly assigned to get 4,000 IU a day for three years lost more bone in their arms than those who got 400 IU a day.12

And those who got 10,000 IU a day lost more bone in their arms and shins than those who got 400 IU a day.

Tell that to CVS.

5. Just two weeks of inactivity takes a toll.

What happens when you’re stuck at home with fewer opportunities to exercise? Even before the coronavirus, researchers wanted to know.

“A lot of work has been done on complete bed rest or immobilization, but little attention has focused on how acute periods of limited activity affect older adults,” says Chris McGlory, assistant professor of exercise metabolism at Queen’s University in Canada.

So he and his colleagues had 22 older overweight people with prediabetes slash their usual steps per day—from 7,000 to about 1,000—for two weeks and then return to their normal activity for another two weeks.13

“We tried to mimic the number of steps someone would take, say, when they stay at home because there’s a flu outbreak or because it’s too cold to go outside, so they’re physically inactive for a number of weeks,” says McGlory.

The results: During the inactive period, “we found an increase in insulin resistance and blood sugar and a decrease in the rate at which muscle proteins were created,” says McGlory. “And none of those things were fully recovered after the two-week period when they returned to their usual activity.”

What if you don’t have prediabetes?

“If you start off without prediabetes, you’d shift toward the prediabetic state, and if you have prediabetes, you’d shift toward the diabetic state,” says McGlory.14

Most older people have already shifted. Among Americans aged 65 or older, 47 percent have prediabetes and another 27 percent have diabetes.15

When it comes to muscle, older people are also at a disadvantage.

“After the fourth or fifth decade of life, we start to lose 1 to 2 percent of our muscle mass per year,” says McGlory.

“And during a period of inactivity, you lose muscle whether you’re young or old. So inactivity combined with the biological loss of muscle is a double whammy for older people.”

What’s more, adds McGlory, seniors don’t regenerate lost muscle as well, “so they don’t recover as quickly as younger people.” Odds are, the participants would have returned to normal if the study had lasted longer, he notes. “But we don’t know how long it would have taken.”

What we do know: staying as active as possible, especially with exercises that build strength, should help.

“If you have stairs in your home, walk up and down to keep up your daily step count,” suggests McGlory. Climbing stairs is ideal because it’s both aerobic and strength exercise.

“You can also do squats and go for a daily walk or jog or cycle within safety guidelines for avoiding coronavirus.”

1Menopause 27: 640, 2020.

2N. Engl. J. Med. 345: 790, 2001.

3PLoS One 2020. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0228773.

4J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 61A: 1059, 2006.

5J. Appl. Physiol. 105: 1498, 2008.

6Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020. doi:10.1093/ajcn/nqaa104.

7JAMA Intern. Med. 178: 530, 2018.

8Br. J. Sports Med. 52: 376, 2018.

9Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 99: 899, 2014.

10Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108: 405, 2018.

11J. Bone Miner. Res. 35: 883, 2020.

12JAMA 322: 736, 2019.

13J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73: 1070, 2018.

14J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98: 2604, 2013.

15 cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf