Potassium salt can cut the sodium and improve health

sleepy cat - stock.adobe.com.

Sodium chloride, or table salt, increases blood pressure, which increases the risk of a heart attack and stroke. Potassium chloride, or potassium salt, adds a salty flavor to foods without contributing to excess sodium. Here’s how potassium salt can help food companies reduce sodium in the American food supply to improve health outcomes and how you can find higher-potassium, lower-sodium products on store shelves.

What is potassium salt?

Potassium chloride is a naturally occurring mineral salt obtained from rock and sea salts. And since it can add a salty taste to foods, potassium chloride (sometimes called “potassium salt” on ingredient lists) is one of the most commonly used sodium chloride (table salt) replacements. In an effort to lower the sodium content of packaged and prepared foods, some manufacturers are replacing a portion of table salt with potassium salt. For home use, some “lite salt” products can be used in cooking and at the table.

The natural presence of potassium in foods supports the safety of potassium chloride in reducing sodium intake; it is considered safe for use in foods in the US and the European Union. Using potassium salt as a salt substitute is a promising solution to improve population health because it reduces sodium intake and increases potassium intake, both of which have been shown to lower blood pressure in randomized clinical trials. Since nearly half of US adults have high blood pressure and most people aren’t consuming enough potassium but far too much sodium, potassium salt could help promote population health.

How potassium salt can benefit public health

Excess sodium intake increases blood pressure. High blood pressure, or hypertension, increases your risk for heart attacks and strokes, and also increases your risk of chronic kidney disease.

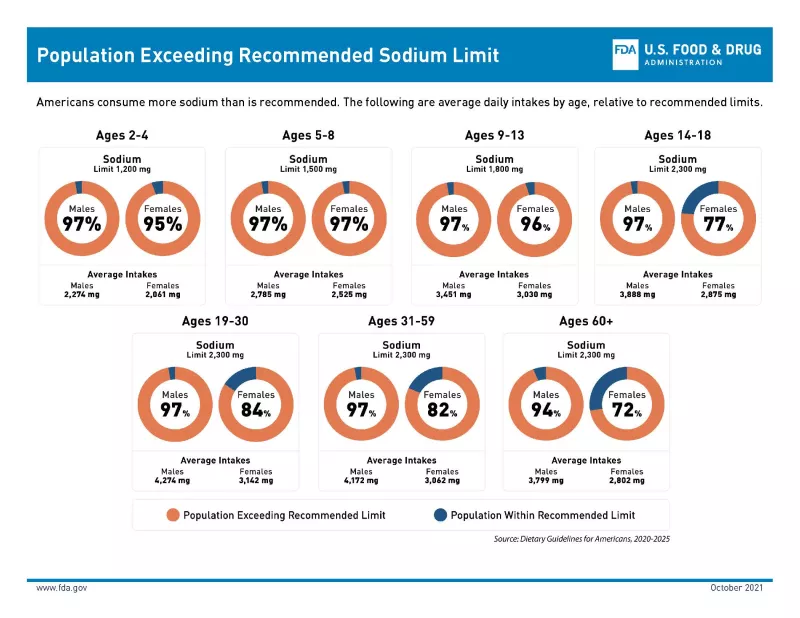

Nearly all Americans eat more than the 2,300 milligrams per day of sodium recommended by the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA 2020-2025); the average American consumes about 3,400 milligrams a day. Approximately 80 percent of American adults eventually develop high blood pressure as they get older. Cutting the sodium in our high-salt diet could prevent thousands of premature deaths every year.

When sodium intake is too high, and potassium intake is too low, the risk for hypertension increases. The World Health Organization suggests that many consumers would benefit from reducing their sodium intake and increasing their potassium intake. Potassium salt may be a significant step toward reducing blood pressure for those at risk for hypertension.

In a 2021 randomized trial, researchers studied 21,000 people in China over age 60 with high blood pressure and a history of stroke. After almost five years, those who were randomly assigned to use a 75 percent sodium chloride and 25 percent potassium chloride salt substitute had a 14 percent lower risk of stroke and 22 percent lower risk of death than those who used only ordinary salt.

That said, certain people should avoid potassium chloride because it poses an increased risk to a small portion of the population who have difficulty excreting potassium.

Certain risks associated with excess potassium

Some people are at higher risk of hyperkalemia, or excess potassium in the blood, which can cause serious heart issues. Many people with excess potassium intake have no symptoms, but sometimes, sudden, extreme changes in potassium intake can cause heart palpitations, nausea, vomiting, and chest pain. People with chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, severe heart failure, older adults, individuals with adrenal insufficiency, and those using medications that impair potassium excretion (like ACE inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, and potassium-sparing diuretics) have an increased risk of hyperkalemia.

Healthy adults and children with normal kidney function are safe to use potassium salt, because they can filter out excess potassium; the rate of hyperkalemia is less than 1 percent of the population, while nearly half of American adults have high blood pressure. If you’re unsure whether a potassium salt substitute is safe for you, speak with your healthcare provider before making the switch.

Potassium salt in the home kitchen

To prevent high blood pressure and increased risk for stroke, replace some ordinary table salt with a potassium-sodium mix and load up on potassium-rich fruits and vegetables. Some people detect a bitter aftertaste from pure potassium salt, so half-sodium, half-potassium salt blends (like Morton Lite Salt) can prevent that downside. And since most people need more potassium anyway, it’s a simple and healthy step most people can take today to benefit your health and decrease your risk of high blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke.

Grocery stores offer a range of salt substitutes, some of which consist almost entirely of potassium chloride and are sodium-free, and some of which are half potassium chloride and half sodium chloride (sometimes called “lite salt”). Simply using a salt substitute instead of table salt can reduce some of your sodium intake without sacrificing flavor.

Some sodium-free potassium salt substitutes have 600 to 800 milligrams of potassium per ¼ teaspoon; adults should get 2,600 to 3,400 mg of potassium daily, so that ¼ teaspoon could contain about a fourth of what you need in a day. A ¼ teaspoon of a “lite salt” typically has 290 mg of sodium—about half what regular table salt has—and 350 mg of potassium. For reference, a small banana has about 360 mg of potassium.

Reducing sodium in the American food supply

We get five percent of our salt from the shaker, five percent from the salt we add when we cook at home, and about 15 percent occurs naturally in foods. That means about 70 percent of our salt intake comes from processed, packaged, and restaurant foods.

That’s where potassium salt could make the biggest impact. In order to meet the FDA’s voluntary sodium reduction targets—and participate in improving population health—the food industry could replace some portion of sodium with potassium salt in packaged foods like bread and snacks, in frozen and fast foods, and even at restaurants. Less sodium and more potassium is a good forward step toward a healthier food supply.

And it’s not difficult to see there’s room for improvement: Comparing different brands of almost any food—salad dressings, breads, packaged meats, pasta sauces—reveals wide disparities in sodium content, which shows that many companies could lower the sodium levels to match the best performers in each category.

Many popular brands already use potassium salt in their products, which you’ll be able to find on the labels as either potassium salt or potassium chloride. Campbell's soups—from classic Tomato and Heart Healthy Cream of Mushroom to newer options like the Well Yes! Spiced Chickpea and Southwest Style Chicken Tortilla soups—get some portion of their salty flavor from potassium salt. Some manufacturers of packaged frozen meals, like Smart Ones, Stouffer’s, and Banquet, have begun using potassium salt in some choices. There are packaged snacks made with potassium salt, including Frito’s Chili Cheese corn chips, Doritos Nacho Cheese, Lay’s Poppables Sea Salt & Vinegar, Flamin’ Hot Cheetos, and many others; while still quite salty, in general, the overall sodium content is reduced with the use of potassium salt.

It's good news that companies making processed, packaged, and frozen food products are aware of potassium salt and are utilizing it already. While most products on this list don’t claim to be low in sodium—they’re not, generally—a step toward reducing the overall sodium content of America’s foods is underway. CSPI encourages these brands and others to continue finding ways to use potassium salt where possible, especially when it can help those companies adopt the FDA’s voluntary sodium reduction targets.

CSPI’s ongoing work to cut the salt

CSPI has been urging the FDA to reduce sodium in the food supply since 1978, when the organization first filed a petition asking for labeling of and limits on sodium in packaged foods. In 2005, after decades of inaction on the part of the FDA, CSPI re-petitioned the agency to set mandatory upper limits on sodium in packaged and restaurant food. In 2015, CSPI sued the FDA over its failure to act, which prompted the FDA to propose voluntary 2- and 10-year sodium reduction targets for processed and restaurant foods in 2016. (CSPI withdrew its lawsuit at that time.) In 2021, the FDA finalized voluntary 2.5-year targets. CSPI again filed a citizen petition seeking longer-term targets in 2023. Finally, in August 2024, the FDA proposed a new round of "Phase II” 3-year voluntary sodium reduction targets for 163 categories of foods. If achieved by the food manufacturing and restaurant industries, Americans’ sodium consumption would be safer and our overall risk for chronic disease would be lower. CSPI will continue to fight for industry to reduce the amount of sodium in our food supply to help Americans live healthier lives.

M.M. Bailey (she/her) is a writer who lives in the DC metro area. Her writing has been featured in Fall for the Book’s October 2021 podcast series and can be found in Fractured Lit, This is What America Looks Like, Furious Gravity, and Grace In Love, among others. Her special interests have focused on cultural representations of gender and race, as well as the role of visual narratives in social justice and reform.

More about sodium

Little evidence of sodium reduction in food supply despite ‘encouraging’ data published by FDA

Sodium

13 foods with more salt, sugar, or fat than you might expect

Healthy Eating

FDA proposes mandatory front-of-package nutrition labels

Food Labeling

Which salt is best? 3 common salt questions, answered

Sodium

Peter’s Memo: Cut the salt

Industry Accountability

Stirring the Pot

Join the fight for safer, healthier food

Sign up to receive action alerts and opportunities to support our work in Stirring the Pot, our monthly newsletter roundup.